A British lawmaker’s proposal to cap whole life emissions on new constructions follows other countries’ similar initiatives – as well as the UK financial sector’s own activity in this area

The UK’s parliament sat for almost two hours to debate the character of its prime minister this week, but just 10 minutes were devoted to a large source of harmful emissions threatening to derail the country’s net zero ambitions: embodied carbon in construction and real estate.

The construction industry emits 40mn to 50mn tonnes of carbon dioxide every year, outstripping aviation and shipping combined. But while one pilot scheme is beginning to provide sustainability-linked finance to green projects based on strict whole-life carbon metrics, experts say the measurements used in some parts of the industry fail even to predict the operational energy requirements of buildings.

Duncan Baker, a member of the ruling Conservative party but not a member of the government, used a parliamentary procedure called a ‘10-minute bill’ on Wednesday to propose legislation he says is already being adopted by other climate-conscious countries around the world.

Led by the Netherlands capping whole life emissions on new constructions in 2018, a number of other countries including Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland, and New Zealand have set out plans for reporting on these emissions, in some cases accompanied by gradually reducing thresholds for new buildings. In France, progressive reductions in this carbon budget will see new buildings required to be 53 per cent more efficient by 2030.

The EU Commission is mulling a bloc-wide requirement to report on these carbon emissions, according to Euractiv, while in the US, state-level limits could be backed up by action from the Biden administration.

“The law in this country places no restriction whatsoever on how much embodied carbon can be emitted when we construct a building,” Baker said in his speech. “We’re decarbonising our electricity grid, we’re ending our reliance on fossil fuels, but we’re leaving ourselves open to a big concrete and steel elephant in the room.”

The UK government’s net zero plan envisions requirements to disclose embodied carbon, with a view to future thresholds. But Baker cited proposals from the construction industry itself as a reason not to delay further: “It’s time to stop putting off embodied carbon as a future area to explore, it’s time now to get embodied carbon regulated.”

Sustainability-linked finance emerges

With UK politicians only now beginning to take buildings’ emissions as seriously as do European peers (the bill passed but now only has a low priority for a second reading), efforts at using the financial sector to encourage low-carbon building have been more innovative.

In November, a £10mn development of six “ultra-sustainable homes” in south London were financed by the Carbonlite Challenge, a pilot project by development finance lender Atelier that incentivises developers with low costs of borrowing.

Developers The Edition Group will get a rebate of more than £200,000 if the Dulwich homes, which include timber construction and planted roofs, meet strict carbon and water limits set in line with a framework built by the Royal Institute of British Architects.

Atelier, which has equity backing from asset management company M&G, has selected a further two developments to lend to, and hopes to commit £25mn by the end of the Carbonlite pilot.

If successful, “we’d then migrate the scheme into a business-as-usual offering – to do that we’d need to raise a green bond”, says founder and joint managing director Chris Gardner, adding that he hopes to include retrofitting initiatives in the project’s scope.

Gardner says sustainability-linked development finance is currently a niche area, but says he hopes interest from both property developers and asset owners providing capital to the company will pick up.

The need for whole-life carbon disclosure

One area for concern, however, is that similar offerings have been developed by other lenders, but based on less rigorous criteria such as the energy performance certificate – potentially channelling green finance into projects with spurious credentials.

“Our competitors’ schemes are all in relation to EPC ratings, and EPCs are certainly better than nothing, but they’re not a lot better than nothing because an EPC rating is simply a thermal rating, it relates to how much energy a property is likely to use,” says Gardner.

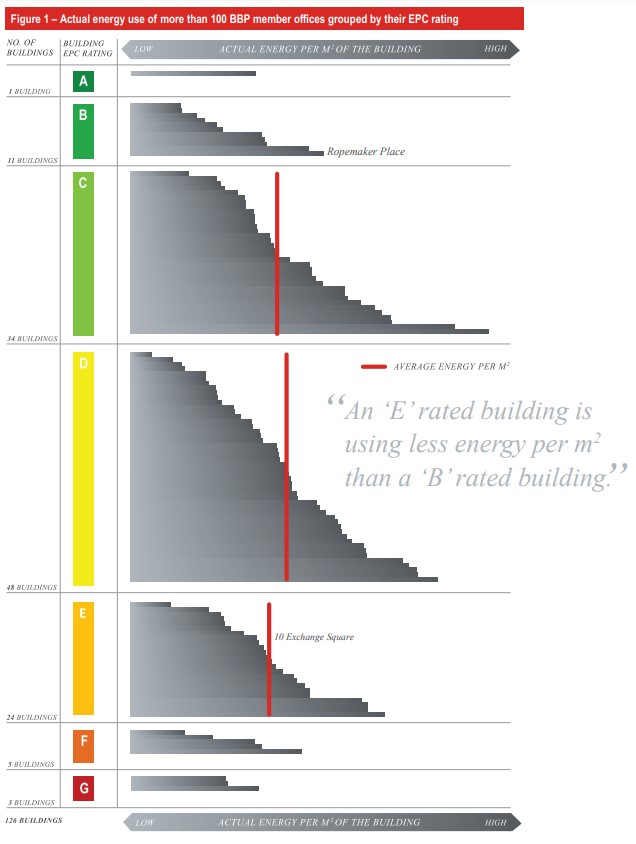

Source: Better Buildings Partnership

In fact, the Better Buildings Partnership, a commercial property owners group, has found there is no correlation between EPC rating and the actual energy use of 100 office buildings. Buildings with E certificates performed better on average than those with B ratings, while the C band was the most energy-intensive.

Even if the scope of these certificates was improved, they still ignore the emissions associated with construction – those targeted by the UK proposed bill and its international equivalents.

Alex Tait, head of technical practice at RIBA, says investors may not yet have become familiar enough with the technicalities of whole-life carbon analysis to begin demanding this standard when assessing an allocation.

“To get to that level you’re really down in the weeds of the construction process,” he says, but adds that he hopes bills such as the one introduced by Baker, and greater investor education, will enable the industry to coalesce around a single standard, then allowing for adequate assessment of progress against net zero goals.

Investors also see the need for harmonised, robust metrics. Douglas Crawshaw, global head of real estate manager research at Willis Towers Watson, says: “Legislation and regulation will assist and drive the agenda here but the need for accurate and complete data will be essential to properly assess progress towards 2050. Consistency (across the globe) on how the metrics are measured and assessed will help accelerate this journey.”

Similar Articles

In Charts: Redemptions drag global climate fund flows to lowest level in four years

In Charts: Canada, Japan, South Korea ‘blocking clean energy transition’ with fossil fuel finance