From measuring impact to allowing individual savers to voice their stance on environmental and social issues, start-up founders are taking sustainable finance head-on

Ask any entrepreneur in financial services about the importance of their product tapping into sustainability issues, and they will likely reveal that it is vital.

Sasha Stancliffe Bird is the co-founder of Supa, a early-stage start-up whose app will aim to show Australian superannuation savers the companies in which they are invested, provide metrics for fund comparison and enable users to change providers if they are unhappy.

Environmental, social and governance issues are not just central to the platform’s ethos of transparency; as one of the few ways of drawing the young demographic it targets into the somewhat fusty world of pensions, they play a driving role in Supa’s success as it courts investment.

“The key problem we set out to solve was poor engagement with retirement savings, particularly amongst a younger age group. People are disengaged with their super, and a key reason for this is the fact that the benefit or reward is far away, intangible,” he says. “ESG, and greater knowledge around what you are investing in more generally, can be used to change this by demonstrating that the money you have invested has a clear impact in the present.”

Increased public awareness of ESG issues is fuelling a wave of similar business launches. Sifted, the Financial Times-backed platform for start-ups, charts more than 800 climate tech companies in Europe alone. Although sustainable finance represents a small percentage of these by funding, entrepreneurs in this sector have plans to redesign the financial system entirely – and have scathing opinions on the practices of established companies.

Tom McGillycuddy, co-founder of impact pension provider and investment app Circa5000, is one such example. A former banker and asset manager, he remains unconvinced by the commitment of some in the sector to solving climate change.

“Some of those companies that I worked for don’t care about it now; they definitely didn’t care about it then,” he says. “ESG is used primarily by the old asset management industry as an excuse not to do anything differently… it’s really about risk mitigation, it’s not about whether the investment’s producing anything to benefit the world.”

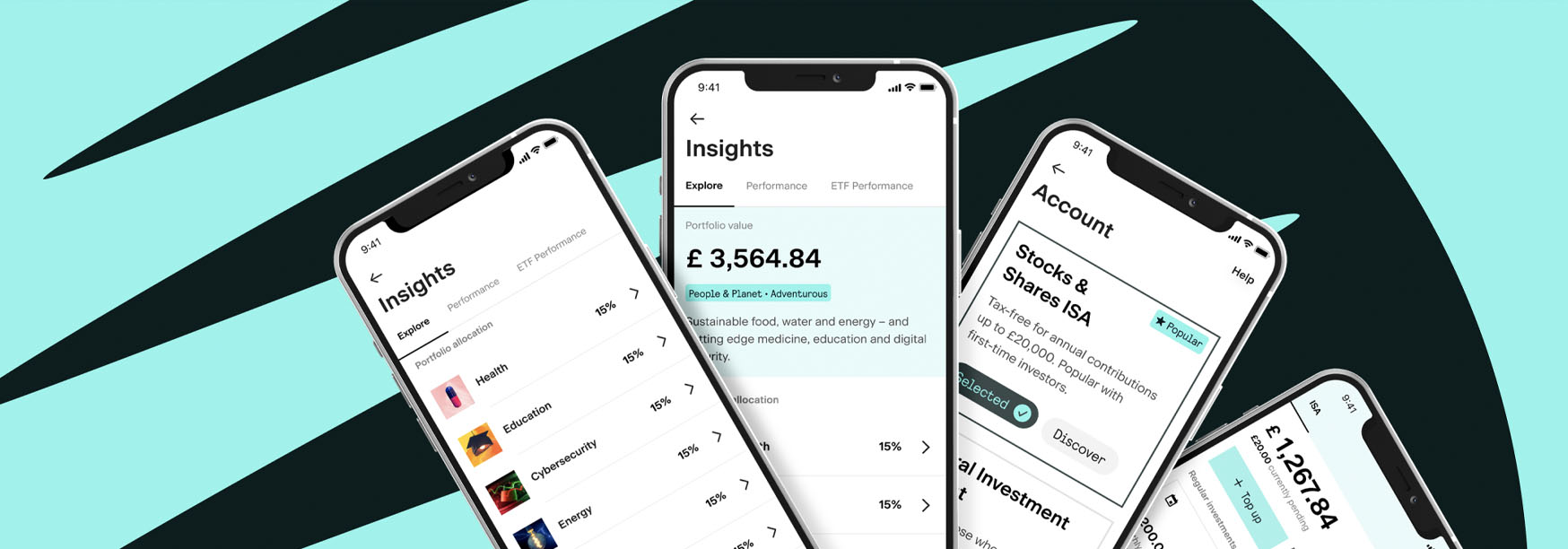

After a stint at an impact fund run by Wellington Management, McGillycuddy set up Circa5000 (formerly Tickr) with co-founder Matt Latham. Initially planned to appeal to like-minded peers in finance, the pair began to see a wider goal of democratising investing.

“We thought the opportunity was actually bigger, and that you could get people to invest for the first time who hadn’t invested before,” McGillycuddy says.

Impact investment strategies have historically played only a small role in balanced portfolios due to their lack of diversification. But Circa5000, which currently offers a mix of third-party exchange traded funds tailored to the user’s risk profile, is now working to “create a solution in listed equity markets which looks and behaves like the general stock market from a risk perspective”.

Bad ESG funds

The goal, says McGillycuddy, is to arrive at a solution that can form “the bulk of an individual’s diversified portfolio” – implicitly driving down the market share of ESG funds, which he lambasts as “the truest form of greenwashing”.

Other disruptors suggest that effective sustainability solutions may lie outside the remit of finance altogether. Yan Swiderski, trustee of the Global Returns Project, advocates a system of “symbiotic wealth management”, where investors allocate a small portion of their portfolio to climate not-for-profits to achieve real change.

Its Global Returns Fund positions itself as a tool for financial advisers to use when building solutions for individuals with strong sustainability preferences, and asset manager TT International has also agreed to allocate a portion of its Environmental Solutions Fund to the GRF. The fund includes climate charities such as Global Canopy and ClientEarth, and takes no fees itself.

“On its own, ESG is not enough, and there’s a lot of disconnect between sustainability-themed funds and real world outcomes,” Swiderski says, pointing to findings by fintech company Util in September 2021 that while sustainable funds minimise net detriment to the environment relative to the total fund universe, neither group effects a positive impact.

He continues: “The idea of symbiotic wealth management is you make a tiny allocation to the best climate solutions, a group of not-for-profits that regenerate the planet, and thereby protect wealth in the sense that all our investments are less risky if the biosphere is protected.”

While these disruptive businesses and charities tend to focus on delivering greater impact than mainstream financial products, leaders of the ESG ‘establishment’ mount a robust defence of their decision to remain engaged with the world’s sin stocks.

UK pension provider Nest was among a coalition of peers that wrote to the Financial Times on February 16 to hit back at criticisms of ‘woke’ capitalism. But chief investment officer Mark Fawcett says he is equally convinced of the need to stay invested and pressure corporate boards, rather than divest and build a portfolio that has positive impact but does nothing to limit environmental or social harms.

“People think that if you divest you’ve solved the problem, but you’ve just sold the problem to someone who might not care. We have more power as shareholders,” he says.

Still, some change is needed. Georgia Stewart is chief executive of Tumelo, a start-up allowing savers to communicate their stance on ESG issues to their savings providers and asset managers. The platform has seen a meteoric rise, with 17 partnerships including Nest and Legal & General, and integration with 75 asset managers.

Stewart calls for ‘ESG 2.0’, where the historic tendency for the investment industry to delegate stewardship must be overturned, with new emerging models either allowing individual savers to directly vote their shares, or requiring asset owners and managers to set policies to which their end users consent.

“That will probably split between the active asset managers who believe, rightly so, that stewardship is part of their value-add, and the passive managers,” she says.

Managers and their clients do not always see eye to eye, and Stewart reveals that while some managers align with saver votes 93 per cent of the time, others are as low as 29 per cent.

But with Tumelo planning its expansion into the retail savings market, and into the US, its disruptive stewardship revolution appears to have firmly taken hold.

“We’re helping their users to not only see what’s in their pension, but also to have a voice,” Stewart says.

Similar Articles

Banks under pressure to reveal data comparing green and fossil fuel spending

With better planning and investment, EV uptake could offer storage and grid flexibility